Since everyone knows that time is money, thanks for “investing” in another Canadian Portfolio Manager blog dedicated to helping you become a better ETF investor. When you put some of your hard-won loonies into a foreign equity ETF, have you ever wondered what the foreign currency exposure means to you? If so, today’s blog is the first in a new series that should pay off handsomely for you. (Or, if you prefer, check out the podcast or YouTube versions below.) Even if it’s not a subject you’ve thought much about, I still think you’ll find it worth your while to learn more.

When it comes to understanding the intricacies of currency conversion, who doesn’t sometimes feel like a Homer? After all, a good doughnut is a lot easier to digest than a detailed lesson in foreign equity exposure.

I remember being thrown head first into the intricacies of currency exchange when I joined PWL Capital in 2007. Back then, currency-hedged foreign equity ETFs were the main options available on the TSX. To obtain unhedged ETF exposure, we first needed to convert Canadian dollars to U.S. dollars before purchasing U.S.-based ETFs on the NYSE or the NASDAQ.

As if that weren’t fun enough, throughout 2007, the Canadian dollar was hovering around par relative to the U.S. dollar. On any given day, I was never sure if $1 CAD was worth $0.98 U.S. … or the other way around. It made my poor Homer head hurt.

I’m not the only one who finds foreign currency exchange to be a head-scratcher. Steven Leong leads product and capital markets for BlackRock’s Canadian ETF business. Here’s his take:

“It seems our human brains are just not fully wired to handle the subject of currency. Even though the math itself isn’t especially hard, I’ve often done currency conversions backwards when building a model. I’ve also seen CFA Charterholders standing around a screen, looking at each other in disagreement over whether the currency had been properly handled. So, for anyone who struggles with currency conversion, know that you’re not alone.”

I hope you’re now feeling much better if you’ve ever found yourself stumped over your ETF’s currency exposure. One of our CPM fans, Marc from Ottawa, was kind enough to send in his excellent question on the subject, which we can now use to explore the matter further.

Specifically, Marc wanted to better understand his currency exposure when purchasing the iShares Core S&P U.S. Total Market Index ETF (XUU) vs. the iShares Core S&P Total U.S. Stock Market ETF (ITOT). XUU is listed in Canadian dollars, while ITOT is listed in U.S. dollars.

Marc asked: “As a Canadian, would it be best for me to hold most of my funds in XUU’s Canadian dollars to avoid currency fluctuations?

Better yet, he provided us with an example to work with:

“Say I buy $30,000 CAD worth of XUU, and it gains 10% in one year – my investment is now worth $33,000 CAD. If I had done the same investment in ITOT (using the Norbert’s gambit strategy to convert my Canadian dollars into U.S. dollars), I would have roughly $21,600 USD with today’s exchange rate of $0.72. If that also gained 10%, it is now roughly $23,760 USD. Meanwhile, during the same year, the Canadian dollar got stronger, and the exchange rate is now $0.80. If I convert this investment back into Canadian dollars, it translates to $29,700, which is less than my original investment in Canadian dollars.”

Thanks to Marc for the relevant currency-related question and detailed example. I could not have queued up the discussion better myself!

If you take away only one thing from today’s post, here it is:

The currency in which your ETF transacts has NO RELATIONSHIP to your ETF’s currency exposure. This holds true whether the currency transaction is in Canadian dollars for XUU or U.S. dollars for ITOT.

Now let’s finetune this central theme.

First, here are Steven Leong’s comments (emphasis mine):

“The short answer here is, you’re investing in an ETF that holds securities that are listed in the U.S., and are priced in U.S. dollars. This means, when the U.S. dollar goes up or down, you are exposed to that fluctuation.

Let’s imagine that the U.S. dollar goes up against the Canadian dollar, while the stock prices themselves don’t change. In that case, the value of XUU has to go up, because its price is quoted in Canadian dollars, and the value of its assets has increased in Canadian dollar terms.

The reverse is true as well. So again, imagine stock prices don’t change, but the U.S. dollar goes down against the Canadian dollar. In this scenario, XUU’s price also has to go down. As a Canadian investor, if you buy a U.S. stock market ETF, then you’re exposed to both the price of the stocks and the U.S. dollar. From a return standpoint, you want them both to go up.”

So, with XUU, ITOT, or any other unhedged U.S. equity ETF, you actually have not one, but two investments. For example, for XUU, your first investment is the U.S. stock market, while your second investment is the U.S. dollar.

Let’s apply this take-away to Marc’s excellent XUU example. So far, Marc had only accounted for the U.S. stock market return of 10%. But XUU is priced in Canadian dollars. So, to determine Marc’s total return, we also need to factor in any U.S. dollar appreciation or depreciation relative to the Canadian dollar. How do we do that? Read on.

At the beginning of the period in Marc’s illustration, $1 CAD was worth $0.72 USD. In forex jargon, your Canadian dollar is your base currency, and your U.S. dollar is your counter currency. This tends to be how most Canadians think about currency conversions: If we have $1 CAD, how many U.S. dollars can we purchase with it?

When wrapping my head around currency fluctuations, I find it easier to make the foreign currency my base currency, and the Canadian dollar my counter currency. So, in Marc’s example, the U.S. dollar becomes my base currency. After all, what I really want to know is: If I have a $1 USD, how many Canadian dollars can I purchase with it?

Adjusting our currency figures in this manner:

Up = good. Down = bad. Call me simplistic, but I find this framework much more intuitive when discussing investment returns.

Now that we’ve established the basics, here’s a slightly technical example to help you become a currency transaction whiz.

In Marc’s illustration, we already know that $1 CAD was worth $0.72 USD at the outset. But suppose I wanted to know how much my $1 USD base currency is worth in my Canadian dollar counter currency? We simply divide 1 by 0.72, which equals $1.3889 CAD. In other words, $1 USD can initially buy $1.3889 CAD.

Now let’s look at the end of the measurement period, when $1 CAD is worth $0.80 USD. Making the same adjustment, we find $1 USD is now only worth $1.25 CAD.

This means the U.S. dollar has depreciated against the Canadian dollar. As Steven mentioned earlier, when holding an unhedged U.S. equity ETF like XUU or ITOT, you want the U.S. dollar to go up or appreciate against the Canadian dollar. The fact that it’s gone down or depreciated is a bad thing, at least from a return standpoint.

So, the currency price is one piece of the equation. What about stock prices? In Marc’s example, the U.S. stock market increased by 10%, while the U.S. dollar depreciated against the Canadian dollar by 10%. Where does that leave you as a Canadian investor?

First, we’ll calculate the U.S. dollar currency depreciation as a simple holding period return. Take the end exchange rate of 1.25, divide it by the beginning exchange rate of 1.3889, and subtract 1 from the result. This gives us –10%, or a 10% depreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to the Canadian dollar.

Next, we’ll take Marc’s first step of increasing XUU’s value by the positive U.S. stock market return of 10%. That is, we multiply Marc’s $30,000 XUU investment by 1 plus the 10% U.S. stock market return to arrive at $33,000.

But then we need to decrease that result by the amount of the U.S. dollar’s depreciation. So, we’ll multiply this figure by 0.9 (1 minus the 10% depreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to the Canadian dollar). $33,000 x 0.9 = $29,700 CAD.

You may also have noticed, $29,700 is the exact same figure Marc correctly calculated for the ending value of his ITOT investment in Canadian dollars.

Voila, the math reflects my earlier theme: The currency in which your ETF transacts has NO RELATIONSHIP to your ETF’s currency exposure. Even though XUU trades in Canadian dollars, and ITOT trades in U.S. dollars, it made no difference to the overall investment returns. At least not after all U.S. dollars were converted back to Canadian dollars.

When you buy XUU with your Canadian dollars, BlackRock needs to convert your loonies to U.S. dollars to purchase XUU’s underlying U.S.-based ETFs (like ITOT) on the NYSE. You don’t actually see BlackRock’s currency conversion taking place. But practically speaking, it’s the same as if you had converted your Canadian dollars to U.S. dollars yourself (using the Norbert’s gambit strategy), and purchased ITOT directly on the NYSE.

If you were guesstimating at outcomes for Marc’s illustration, you may have assumed a 10% U.S. stock market increase accompanied by a 10% U.S. dollar depreciation should be a wash. Ten up, ten down. Why don’t they just offset one another, rather than result in the decrease from $30,000 CAD to $29,700 CAD?

It turns out, you can’t simply net out your foreign stock market returns and currency returns. You need to chain-link them together. This is a complicated way of saying: “Add 1 to each return, multiply them together, and subtract 1 from the end result”.

So, let’s do that. We’ll add 1 to our +10% stock market return, to give us 1.1. Then we’ll add 1 to our –10% U.S. dollar currency return, to give us 0.9. Multiply 1.1 x 0.9 to come up with 0.99, and subtract 1 from this result. This equals a total return of –1%.

So, after a positive 10% U.S. stock market return and a negative 10% U.S. dollar return, you are not made whole. You have actually lost 1% of your portfolio value. This is why Marc’s $30,000 investment is now worth only $29,700. He still lost 1% of the initial value of the fund, or $300.

Let’s wrap with one more demonstration of how XUU and ITOT have similar U.S. stock market and U.S. dollar exposure, even though they transact in different currencies.

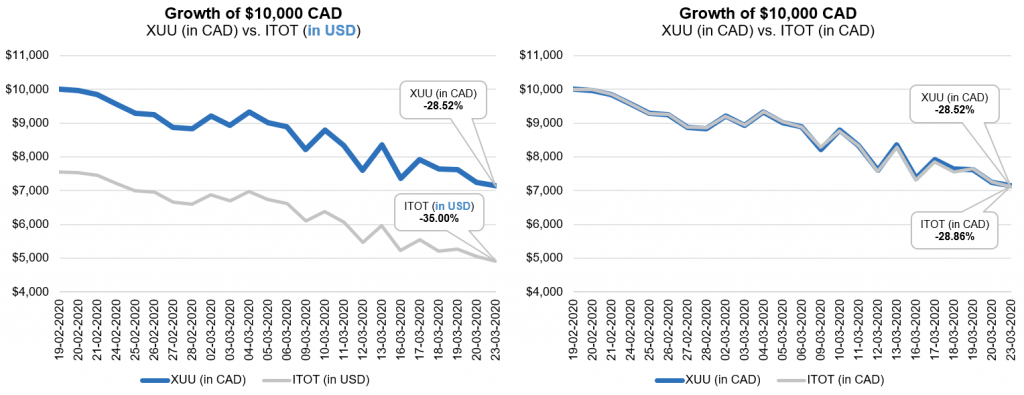

We’ll leave Marc alone now, and consider two Canadian buddies, Bill and Ted. Each have $10,000 CAD they would like to invest in either XUU or ITOT. Unfortunately, their timing couldn’t be worse. They both decide to invest their cash at the top of the market on February 19, 2020.

Bill, doesn’t want to deal with currency conversions, so he decides to purchase XUU with his $10,000 CAD. Immediately following the purchase, his XUU holdings plummet, before finding a bottom of $7,148 CAD on March 23, 2020. Bill loses around 29%, at least on paper.

Ted starts by converting his $10,000 CAD to $7,558 USD at an exchange rate of 1.3231. He then purchases ITOT with his U.S. dollars on February 19th, and watches in horror as the fund loses 35% of its value in U.S. dollar terms. Ted bottoms out at $4,913 USD on March 23rd, with his ITOT holdings dropping by an extra 6% relative to Bill’s XUU holdings.

Since he has not yet come to terms with today’s lesson on currency exposure, Ted instantly regrets his decision. On March 23rd, he sells his entire ITOT holding and converts his $4,913 USD back to $7,114 CAD at the then-current exchange rate of 1.4482. Maybe the lightbulb finally comes on for Ted when he is pleasantly surprised: After the reconversion, he realizes he actually has almost as many loonies as his buddy Bill, and he has also lost only around 29% in Canadian dollar terms.

In short, Bill and Ted benefited about equally from their foreign currency exposure. Because the U.S. dollar appreciated by 9.5% against the Canadian dollar, it helped save their Canadian bacon. Due to similar U.S. stock market and currency exposure in both XUU and ITOT, both holdings fell by nearly 29% in Canadian dollar terms. This represented a 6% improvement over the overall U.S. stock market drop of 35%. Although Ted didn’t realize the currency benefit on paper until he converted his U.S. dollars back to Canadian, it was there all along during his most excellent currency adventure.

So far, our examples have focused on one (U.S.) foreign stock market with one underlying currency. In our next post, we’ll take our currency conversion on the road. You’ll discover that the same concepts apply equally as well to ETFs that invest in multiple foreign stock markets.