Before the release of all-purpose asset allocation ETFs, many Canadian index investors built their ETF portfolios using three funds, including:

Even though you can now conquer the world (or at least invest in it) with a single asset allocation fund, many of you may still prefer the three-ETF approach. Maybe the control freak in you can’t quite embrace investing in just one fund—even if it supposedly does it all for you. Or maybe you’d prefer to tweak your equity home bias. Rather than sticking with the 25%-30% Canadian equity allocation found in many asset allocation ETFs, you may still want to tinker with your domestic vs. foreign stock mix by holding different funds for each.

For whatever reason, let’s say you’re sticking with a three-fund portfolio. Which global equity fund is right for you? Fortunately, there are really only two ETFs that deserve your attention:

If you’re short on time, here’s today’s compelling conclusion on how to choose from this menu of two: With the exception of one minor detail related to XAW’s U.S. equity holdings, it doesn’t really matter. They’re both solid choices, with such minor differences, you’re unlikely to go horribly wrong either way.

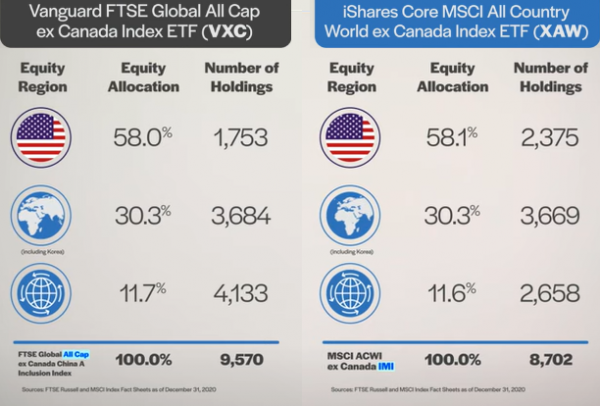

When it comes to asset allocation, either VXC or XAW offer you broadly diversified foreign equity exposure in relatively equal measures, with seemingly similar asset class ratios.

Both indexes tracked by VXC and XAW include thousands of large-, mid-, and small-cap companies. We know this, because of the “All Cap” and “IMI,” or “investable market index,” in their names. Both terms suggest you’re investing in the same world of globally diversified, ex-Canadian investments. And each fund allocates this world in a similar fashion.

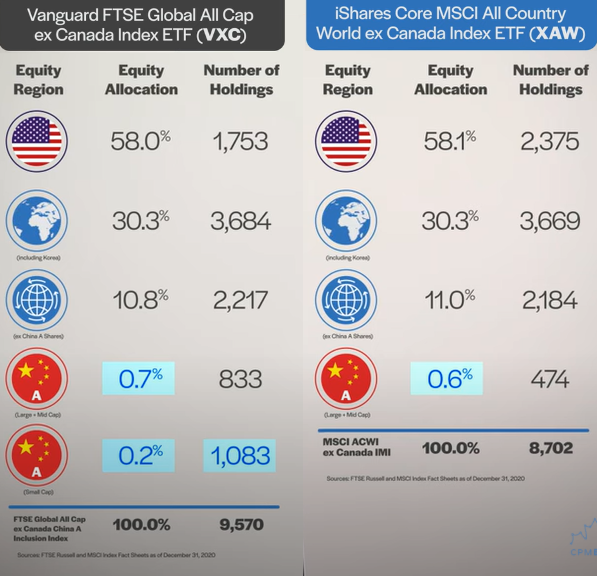

We now know VXC and XAW will provide similar market exposure and plenty of diversification. But there are some small differences in how each fund allocates shares of companies located in China: more specifically, China A shares.

China A shares trade on the China mainland, are denominated in Renminbi, and make up just under half of China’s investable stock market. Until very recently, they were excluded from both the FTSE and MSCI global equity indexes. That’s no longer the case today, and there are a couple of seemingly noteworthy differences between how the two funds manage their China A share allocations.

At a glance, these differences seem like a big deal. In reality, China A shares end up representing such a tiny portion of each index, I don’t see a compelling reason to prefer either fund at this time.

If we dig a little deeper, we’ll see why.

While inclusion rates are expected to increase over time, MSCI’s emerging markets indexes currently include only 20% of the China A shares market cap. FTSE has a slightly higher inclusion rate of 25% (both MSCI and FTSE inclusion weights are as of December 31, 2020). With these ratios in mind, here’s what happens if we separate China A shares from the general emerging markets allocation:

In other words, FTSE’s greater diversification into China A shares turns out to be more of a red herring than a distinction worth fishing for.

Lower fees are often another strong argument for favoring one fund over another. But once again, if we crunch the current costs, we find neither ETF has an edge.

For years, VXC had lagged behind XAW on both fees and tax-efficiency. But in November 2019, Vanguard lowered VXC’s management expense ratio from around 0.27% to just 0.21%. This is comparable to XAW’s MER of 0.22%.

VXC also used to be less tax-efficient than XAW. For its international equity allocation, it held two U.S.-based ETFs: The Vanguard FTSE Europe ETF (VGK) and the Vanguard FTSE Pacific ETF (VPL). This combination created an extra layer of foreign withholding taxes across all account types, with an expected unrecoverable foreign withholding tax ratio of around 0.45% per year in RRSP and TFSA accounts.

XAW, on the other hand, gains its international equity exposure from the iShares Core MSCI EAFE IMI Index ETF (XEF), which is a Canadian-based ETF that holds the international stocks directly. This creates one less layer of withholding taxes, resulting in a foreign withholding tax ratio of around 0.32% per year when held in an RRSP or TFSA.

But again, in November 2019, VXC dumped VGK and VPL. It replaced them with the Vanguard FTSE Developed All Cap ex North America Index ETF (VIU), a Canadian-based ETF that holds the international stocks directly.

As a result, VXC and XAW both had the same foreign withholding tax ratio of 0.32% in 2020, which implies similar tax-efficiency for both going forward. It would appear that neither ETF has the edge on product costs or foreign withholding taxes.

We’ve saved the best anti-climactic comparison for last. When you buy an index fund, you expect it to closely track its index (after fees, of course). Hence the name, “index fund”. But during 2020, XAW lagged its index by more than 2%, while VXC lagged its index by just 0.5% over the same period.

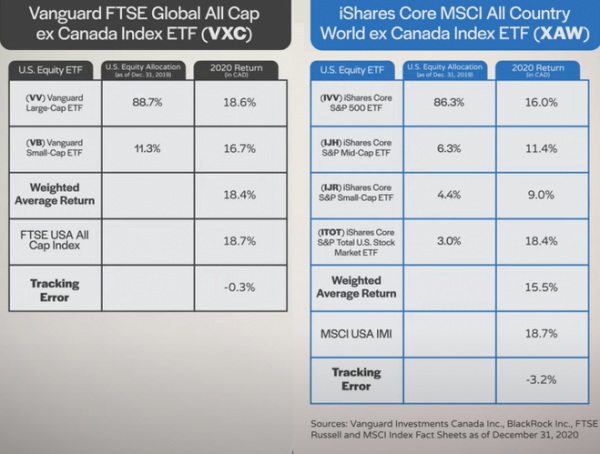

As we’ll explain next, XAW hit some tracking error headwinds in 2020, due to its decision to select slightly more actively managed U.S. equity ETFs. Here’s what happened …

As mentioned earlier, XAW tracks the MSCI All Country World ex Canada Investable Market Index. What we did not mention is XAW is actually a fund-of-funds, holding multiple ETFs to approximately track its foreign equity index.

XAW’s U.S. equity component follows the MSCI USA Investable Market Index. But there are no ETFs tracking this index, so iShares had to get creative. They could have shot for “close enough” with one broad U.S. equity ETF like the iShares Core S&P Total U.S. Stock Market ETF (ITOT). Instead, they have decided to hold four U.S. equity ETFs, hoping to reduce XAW’s index tracking error.

Unfortunately, the attempt had the opposite effect in 2020, because three of the S&P ETFs are not entirely passive. Instead of just tracking every company within the asset class, each index chooses from a representative sample of the whole. Based on numerical restraints, a committee selects which companies’ stocks are included or excluded:

With their respective 500-, 400-, and 600-company limits, these indexes ended up excluding a number of U.S. stocks that happened to shoot the lights out in 2020. Most notably, there’s Tesla. Even though it returned over 700% in Canadian dollar terms, Tesla was excluded from the S&P MidCap 400 Index throughout 2020, and was only added to the large-cap S&P 500 Index toward year-end. These exclusions caused the U.S. equity component of XAW to underperform its MSCI USA IMI benchmark by around 3.2% in 2020.

Ironically, XAW could have simply held ITOT for its core U.S. equity holding, and significantly reduced its short-term tracking error. Following a passively managed broad-market U.S. equity index, ITOT doesn’t have the same company selection constraints. In other words, rather than trying to choose a representative batch, it simply tracks the entire lot.

Of course, Vanguard faced similar challenges in 2020. There is also no U.S. equity ETF that follows the FTSE USA All Cap Index. However, Vanguard’s selections didn’t suffer from the same S&P committee conundrum. Instead, they’ve combined two existing Vanguard ETFs for a more purely passive approach:

So, we now know that XAW had a brutal 2020 tracking error compared to its index. But is the one-year stumble a good enough reason to dump or avoid the fund? If we look longer-term, we’ll see the jury is still out on who the true tracking-error champ is.

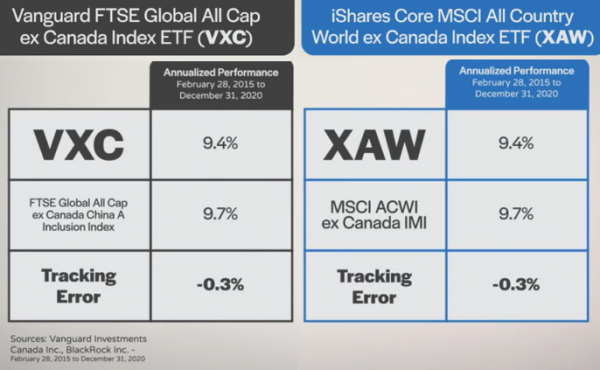

Since the first full month of its launch in March 2015 through December 2020, XAW returned 9.4% annualized. Over that same period, the MSCI All Country World ex Canada Investable Market Index returned 9.7%. That’s a tracking error of negative 0.3%. This seems reasonable, as XAW’s MER would be expected to cause tracking error of at least negative 0.22%.

And what about VXC? Well, it also returned 9.4% annualized over the same period. And its underlying index also returned 9.7%. So, its tracking error was an identical negative 0.3%.

In other words, even with XAW’s recent stumble, both XAW and VXC had comparable returns and tracking error to their index over the past 5+ years.

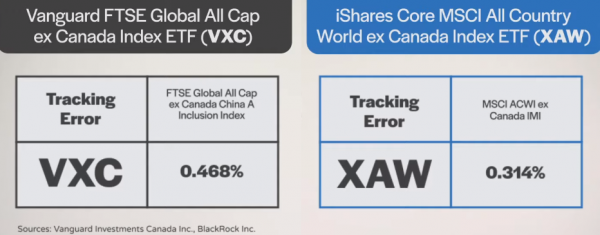

But what if we calculate the monthly tracking error for each fund between March 2015 and December 2020? Tracking error is commonly used to describe a fund’s annual outperformance or shortfall relative to a benchmark. But in this more technical definition of tracking error, we’ll calculate the standard deviation of the differences in their monthly returns. Just remember, the lower the historical tracking error, the more closely an ETF has tracked its index.

For VXC and its index, we find a very low tracking error of 0.468%. Over the same period, XAW and its index had a tracking error of 0.314%, indicating an even tighter tracking error.

So, by this measure, even though XAW underperformed its benchmark in 2020, XAW actually has had a lower—not higher—tracking error to its index than VXC has had to its own. At least historically, we can’t claim that XAW has had poor tracking error to its index since inception. That’s just not true.